Logistics Meaning and Definition

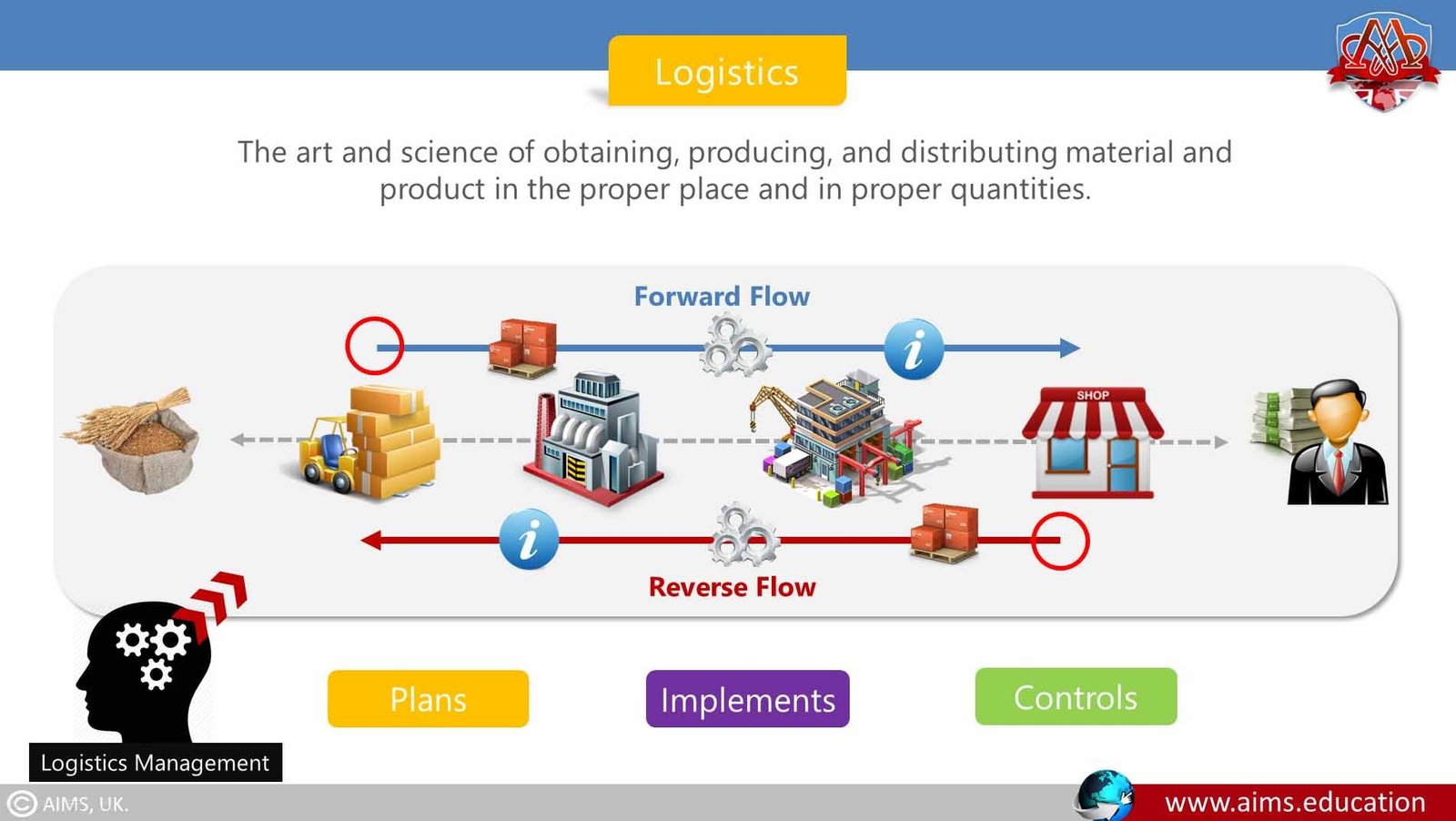

Logistics meaning is “the activity of transporting commercial goods to customers”, and logistics definition may be given as “The art and science of obtaining, producing, and distributing material and product in the proper place and in proper quantities.” It is a rapidly evolving business discipline that involves the management of order processing, warehousing, transportation, materials handling, and packaging—all of which should be integrated throughout a network of facilities. The below video gives a full understanding of what is logistics management.

Our Supply Chain Programs

Complexity of Logistics Management

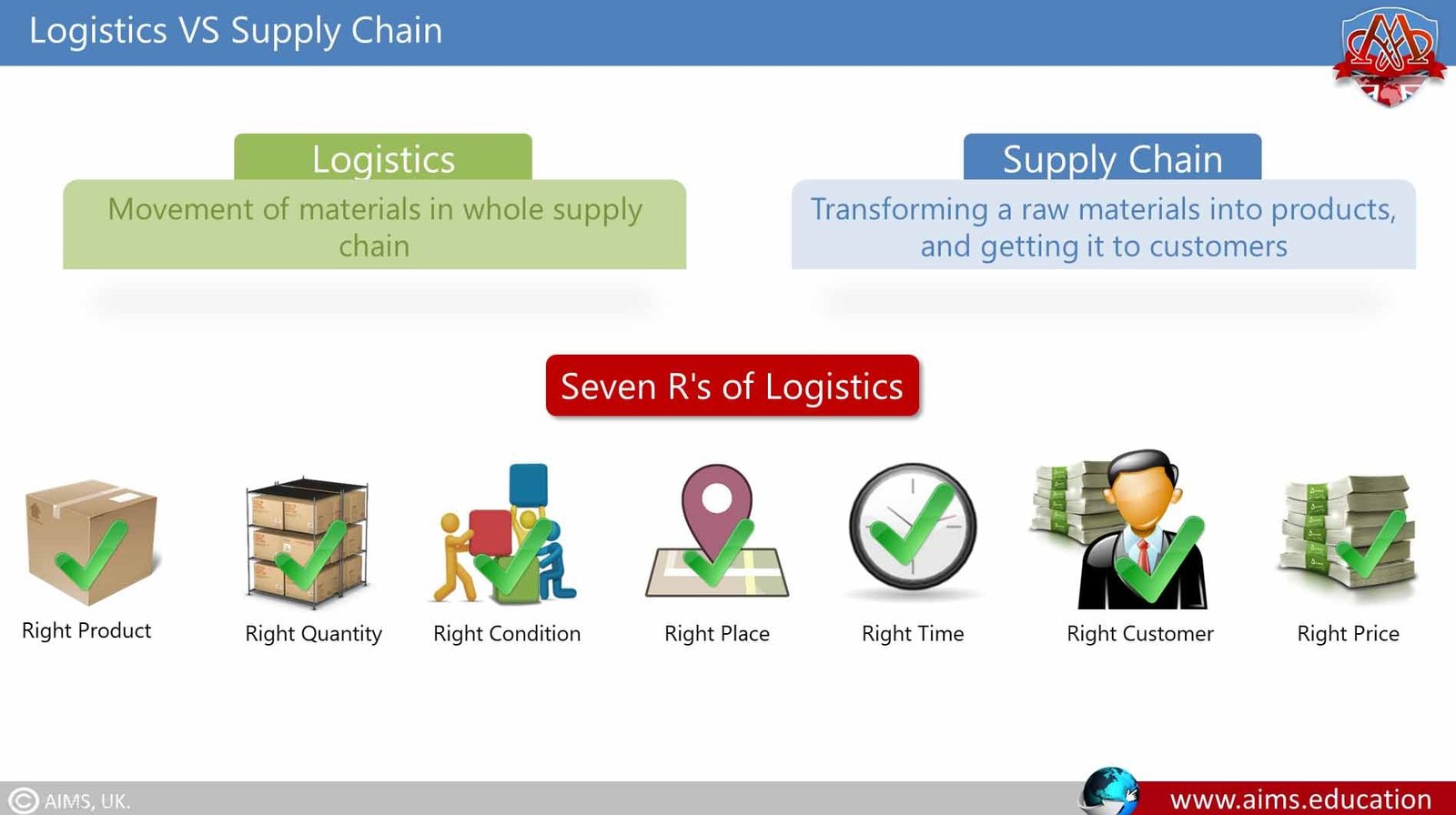

Now, that’s a tall order! Although logistics has been performed around the globe since ancient civilizations were at war with one another, we’re still learning and trying to become experts at managing it. Despite the research and progress that’s been made, logistics is still one of the most dynamic and challenging operational areas of Supply Chain Management. To understand logistics meaning at the most basic level, we must know that logistics management includes the various related tasks required to get the right goods to the right customers at the right time. Others tout a broader definition: getting the right product in the right quantity and right condition at the right place at the right time for the right customer at the right price.

1. The Continuous Nature of Logistics Operations

No other function in the supply chain is required to operate 24 hours a day, seven days a week from New Year’s Day to New Year’s Eve—there are no days off. That is why customers often take logistics for granted; they have come to expect that product delivery will be performed as promised. But it’s not that simple, as you will learn. It can be expensive and takes expertise.

2. Cost of Logistics Services

Logistics management adds value to the supply chain process if inventory and procurement are strategically positioned to achieve sales. But the cost of creating this value is high. According to the 19th annual “State of Logistics Report” by the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals, published in 2008, United States companies spent US$1,398 billion on logistical services. Transportation costs ran US$857 billion, and that constituted nearly 62 percent of total reduced logistics costs.

3. Transportation – a Major Contributor to Logistics Operation:

As these statistics indicate, transportation is the largest contributor to logistics costs: the movement of raw materials to a processing plant, parts to a manufacturer, and finished goods to wholesalers, retailers, and customers. But getting the goods from one point to another requires performing a number of other shipment-related functions. Goods need to be packaged, loaded, unloaded, warehoused, distributed, and paid for whenever they change hands.

Supply chain partners must efficiently and effectively carry out these logistical tasks to achieve a competitive advantage. This may require mastery of languages, currencies, divergent regulations, and various business climates and customs in an increasingly global market.

4. Logistics Challenges

Defining logistics precisely presents a challenge. Everyone agrees that logistics management is (or should be) a part of supply chain management. As Douglas Long writes, “Supply chain management is logistics taken to a higher level of sophistication.” The exact line of demarcation between the two management systems is understandably vague.

5. Role of Inventory and Forecasting in Logistics

In their classic text “Supply Chain Logistics Management”, authors Bowersox, Closs, and Cooper include several functions that are treated outside the logistics section of this course, such as forecasting and inventory management. Some authorities may place those two functions within the scope of logistics management, while others may not. Still, all agree that inventory and forecasting must be considered when designing an effective supply chain network, and efficient system for moving goods quickly from place to place.

6. What is Logistics Management in Supply Chain Management?

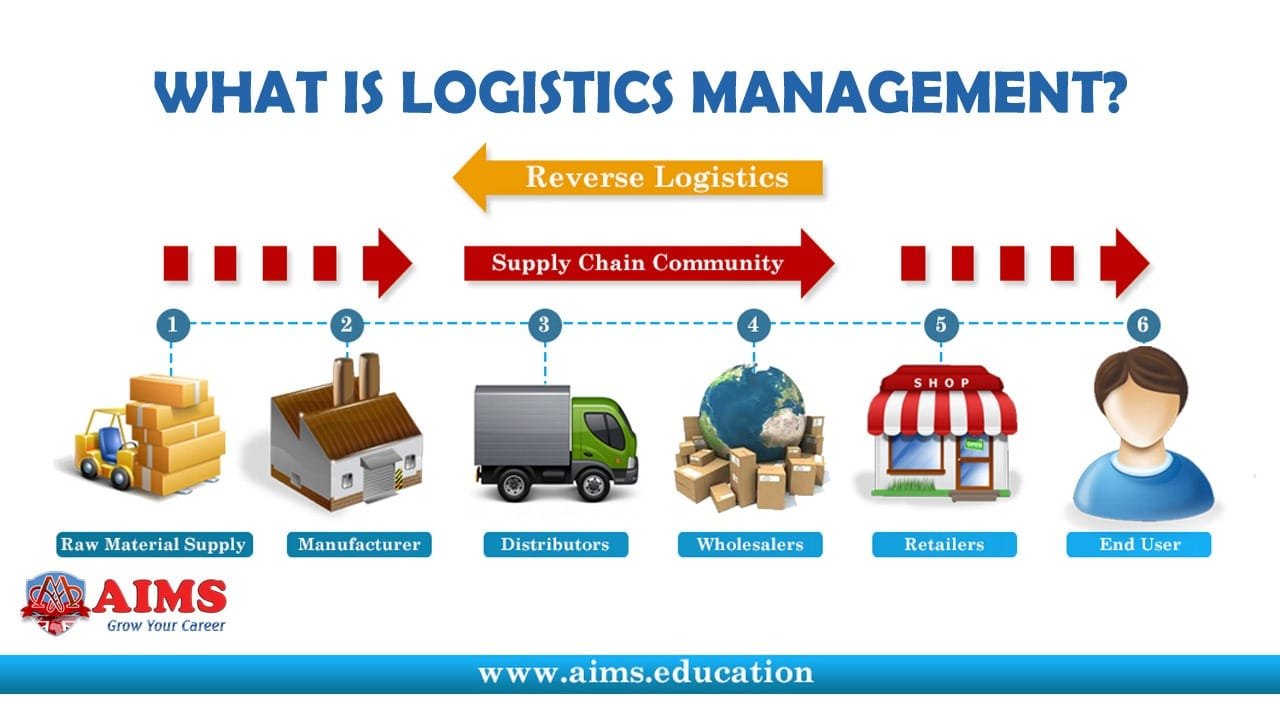

The supply chain is about “moving”—or “transforming”—raw materials and ideas into products or services and getting them to customers. Logistics may be defined as moving materials or goods from one place to another. In that sense, logistics is the servant of design, production, and marketing. But it can bring added value by quickly and effectively doing its job. The following areas of logistics management contribute as an integral part of supply chain management.

5 Key Areas in Logistics Management

Five areas contribute to an integrated approach to logistics within SCM. They are:

- Inventory Management;

- Transportation Management;

- Warehousing;

- Order Fulfillment; and;

- Demand Planning.

Two Key Components of Logistics

1. Transportation

Many modes of transportation play a role in the movement of goods through supply chains: air, rail, road, water, pipeline. Selecting the most efficient combination of these modes can measurably improve the value created for customers by cutting delivery costs, improving the speed of delivery, and reducing damage to products.

2. Warehousing

When inventory is not moving between locations, it may have to spend some time in a warehouse. Warehousing is “the activities related to receiving, storing, and shipping materials to and from production or distribution locations. It is a very important factor, and we must consider knowing the logistics’ meaning.”

Major Types of Logistics

1. Third- and Fourth-Party Logistics

Like other aspects of supply chain management, the various logistics functions can be outsourced to firms specialising in some or all of these services. Third-party logistics providers (3PLs) actually perform or manage one or more logistics services. Fourth-party providers (4PLs) are logistics specialists and play the role of general contractor by taking over the entire logistics function for an organization and coordinating the combination of divisions or subcontractors necessary to perform the specific tasks involved. This growing trend in the logistics business incorporates the supply chain management philosophy of concentrating on core competencies and partnering with other firms to perform in areas outside your competence.

2. Reverse logistics

Another growing area of supply chain management is reverse logistics, or how best to handle the return, reuse, recycling, or disposal of products that make the reverse journey from the customer to the supplier. This business can be handled at a loss, or it can actually become a profit center.

What is Logistics Management Value Proposition?

Being able to match key customer expectations and requirements to your firm’s operating competency level and customer commitment is the essential ingredient in optimizing the value of logistics. The logistics value proposition stems from a unique commitment of your firm to an individual customer or select group of customers. The value stems from your ability to know exactly how to balance logistics costs against the appropriate level of customer service for each of your key customers.

So, you’ll need to determine the exact recipe and proportion of ingredients to meet a particular customer’s logistical expectations and requirements. How will you know when you’ve got the right balance? If you keep in mind that logistics must be managed as an integrated effort to achieve customer satisfaction at the lowest total cost, then it makes sense that service and cost minimization are the key elements in this proposition.

1. Understanding the Economics of Logistics

What company hasn’t had to pay a painfully high price to ship a product overnight to meet a deadline of some sort? It can be done, but it’s not fiscally prudent. Similarly, any level of logistical service can be achieved if a company is willing and able to pay for it. So technology isn’t the limiting factor for logistics for most companies—it’s the economics.

For Example

What does it cost to keep the service level high if a firm keeps a fleet of trucks in a constant state of delivery readiness or it keeps dedicated inventory for a high volume customer that can be delivered within minutes of receiving an order. How do you decide if that’s money well spent?

The key is to determine how to outperform competitors in a cost-effective manner. If a table manufacturer needs a specific type of wood to produce all its table legs but that wood type is not available, it may force the plant to stop or close down until the material arrives, thereby incurring expensive delays, potential lost sales, and decreased customer satisfaction. In contrast, if a home improvement store experiences a one-day delay in inventory replenishment of 20-watt night-light bulbs at its warehouse, the impact on profit and operational performance will likely be very low and insignificant.

In most situations, the cost-benefit impact of a logistical failure is directly related to the importance of the service to the customer. When a logistical failure will significantly impact a customer’s business, error-free logistics service should receive higher priority. Such service implies that the customer’s order was complete, delivered on time, and consistently correct over time.

2. Total Cost of Logistics in Cost Minimization

The second element of the value proposition, cost minimization, should be interpreted as the total cost of logistics in order to be accurate. The total cost of logistics is “the idea that all logistical decisions that provide equal service levels should favour the option that minimizes the total of all logistical costs and not be used on cost reductions in one area alone, such as lower transportation charges.”

For many decades, the accounting and financial departments in organizations sought the lowest possible cost for each logistical function, with little or no attention paid to integrated total cost trade-offs. As they learned later, that did not work very well. So, today’s leading supply chain companies have developed functional cost analysis during supply chain analysis, supply chain risk management, and activity-based costing activities that accurately measure the total cost of logistics. The goal now is for logistics to be cost-effective as determined by a cost-benefit analysis, considering how a logistical service failure would impact a customer’s business.

3. Importance of Certification and Education in Logistics Management

A robust foundation in logistics often begins with formal qualifications. Courses such as a diploma in logistics offer students the necessary skills to handle challenges. An MBA in supply chain and logistics management provides insights into logistics and supply chain operations and supply chain strategies. For those aiming for high-level strategic roles, a doctorate in logistics management can be a viable option. Obtaining a CSLP logistics certification can develop expertise in individuals seeking to enter the logistics industry.

Logistics Goals and Strategies

At the highest level, logistics management shares the goal of supply chain: “to meet customer requirements.” There area number of logistics goals that most experts agree upon:

- Respond rapidly to changes-in the market or customer orders.

- Minimize variances in logistics service.

- Minimize inventory to reduce costs.

- Consolidate product movement by grouping shipments.

- Maintain high quality and engage in continuous improvement.

- Support the entire product life cycle and the reverse logistics supply chain.

An effective logistics management strategy depends upon the following tactics:

- Coordinating functions (transportation management, warehousing, packaging, etc.) to create maximum value for the customer;

- Integrating the supply chain;

- Substituting information for inventory;

- Reducing supply chain partners to an effective minimum number and;

- Pooling risks.

We’ll analyze each of these tactics.

1. Coordinating Functions

Interconnectedness of Logistics Systems

Logistics can be viewed as a system comprising interlocking, interdependent parts. From this perspective, improving any part of the system must be done with full awareness of the effects on other parts. Before the advent of modern logistics management, however, the various operations contributing to the movement of goods were usually assigned to separate departments or divisions, such as the traffic department. Each area had its own separate management and pursued its own strategies and tactics.

2. Functional Decisions in Logistics

Decisions made in any one functional area, however, are very likely to affect performance in other areas, and an improvement in one area may very well have negative consequences in another unless decisions are coordinated among all logistics areas. Adopting more efficient movement of goods, for example, may require rethinking the number and placement of warehouses. Different packaging will almost certainly affect shipping and storage. You may improve customer service to a level near perfection but incur so many additional expenses in the process that the company as a whole goes broke.

You need a cross-functional approach in logistics, just as you do in supply chain management as a whole. Teams that cross functions are also very likely to cross company boundaries in a world of international supply chains with different firms focused on different functions.

True Value of Logistics Management

The overall goal of logistics management is not better shipping or more efficient locations of warehouses but more value in the supply network as measured by customer satisfaction, return to shareholders, etc. There is no point, for instance, in raising the cost of shipping—thus, the price to the customer—to make deliveries faster than the customer demands. Paying more to have a computer delivered today rather than tomorrow may not be a tradeoff customers want to make. However, getting a still-warm pizza delivered in less than 20 minutes might be worth a premium price (and a tip). Fast delivery, in other words, is not an end in itself, and the same is true of any aspect of logistics management or supply chain management.

3. Integrating the Supply Chain

Integrating the supply chain requires a series of steps when constructing the logistics network. In a dynamic system, steps may be taken out of order and retaken continuously in pursuit of quality improvements; the following list puts the steps in logical order.

a. Locat in the Right Countries

- Identify all geographic locations in the forward and reverse supply chains.

- Analyze the forward and reverse chains to see if selecting different geographic locations could make the logistics function more efficient and effective. (Not all countries are equal regarding relevant concerns such as infrastructure, labor, regulations, and taxes).

b. Develop an Effective Import-Export Strategy

- Determine the freight volume and number of SKUs (stock-keeping units) that are imports and exports.

- Decide where to place inventory for strategic advantage. This may involve deciding which borders to cross and which to avoid when importing and exporting and determining where goods should be stored in relation to customers. (Some shipping companies now add a “war risk surcharge” if required to pass through or near a nation with civil unrest or at war.) Both geographic location and distance from the customer can affect delivery lead times.

c. Select Warehouse Location

- Determine the optimal number of warehouses.

- Calculate the optimal distance from markets.

- Establish the most effective placement of warehouses around the world.

d. Select Transport Modes and Carriers

Determine the mix of transportation modes that will most efficiently connect suppliers, producers, warehouses, distributors, and customers.

e. Select the Right Number of Partners

Select the minimum number of firm freight forwarders using smart logistics techniques and 3PLs or a 4PL to manage forward and reverse logistics. In selecting logistics partners, also consider their knowledge of the local markets and regulations.

f. Develop State-of-the-Art Information Systems

Reduce inventory costs by more accurately and rapidly tracking demand information and the location of goods. Developing state-of-the-art information systems may be difficult in some regions, making defining the processes and information flows even more critical.

4. Substituting Information for Inventory

Physical inventory can be replaced by better information in the following ways:

- Improve communications

- Talk with suppliers regularly and discuss plans with them.

- Collaborate with suppliers.

- Use HT to coordinate deliveries from suppliers. Remove obsolete inventory. Use continuous improvement tools and share observations about trends.

- Track inventory precisely.

- Track the exact location of inventory using bar codes and/or RFID (radio frequency identification) with GPS (global positioning systems).

- Keep inventory in transit.

It’s possible to reduce systemwide inventory costs by keeping inventory in transit. One method of keeping inventory in motion for the maximum amount of time is a distribution strategy called cross-docking. Used with particular success by Wal-Mart, cross-docking involves moving incoming shipments directly across the dock to outward-bound carriers. The inventory thus transferred may literally never be at rest in the warehouse.

Example: Cross-Docking in the Airline Industry

Another example of cross-docking can be taken from the airline industry. When a passenger travels from Seattle to New York, he or she might be cross-docked in Chicago. The airline configures its network this way instead of having direct flights from city to city. Passengers are not warehoused per se but simply pass through the airport in an hour or two, getting off one plane and onto another. At the end of the day, ideally, the airport should be empty, as should all cross-docking locations.

A trailer, railcar, or barge can be considered a kind of mobile warehouse. GPS should closely track rolling inventory to facilitate rapid adjustments if a shipment is delayed or lost or a customer changes an order at the last minute.

a. Use postponement centers

To avoid filling warehouses with the wrong mix of finished goods, set up postponement centers to delay product assembly until an actual order has been received.

b. Mix shipments to match customer needs.

Match deliveries more precisely to customer needs by mixing different SKUs on the same pallet and by mixing pallets from different suppliers.

c. Don’t wait in line at customs

Reduce the time spent in customs by clearing freight while still on the water or in the air.

5. Reducing Supply Chain Partners to an Effective Number

Though you have to watch out for tradeoffs in effectiveness when knowing what is logistics and reducing the number of logistics partners, you can generally increase efficiency by doing so. If possible, look for an entire echelon (tier) you can do without, such as all the wholesale warehouses or factory warehouses.

The more partners there are in the chain, the more difficult and expensive the chain is to manage, so use the best supply chain practices. Handoffs among partners cost money and eat up time. Having many partners means carrying more inventory. Reducing the number of partners can reduce operating costs, cycle time, and inventory holding costs. There is, however, some lower limit below which you create more problems than you solve. If you eliminated all partners other than your own firm, you’d be back to the vertical integration strategy pursued in a simpler marketplace during the early 20th century by U.S. auto-maker Henry Ford.

6. Pooling Risks in Logistics Management

Regarding inventory management, pooling risks is a method of reducing stockouts by consolidating stock in centralized warehouses. The risk of stockouts increases as supply chains reduce the safety stock held at each node and move toward Just-in-Time ordering procedures. With every entity attempting to keep inventory costs down in this manner, the risk of stockouts rises if buying exceeds expectations. Statistically speaking, when inventory is placed in a central warehouse instead of in several smaller warehouses, the total inventory necessary to maintain a level of service drops without increasing the risk of stockouts. An unexpectedly large order from any customer will still be small in terms of the total supply available. So, use the supply chain risk management techniques.

Risk pooling also works with parts inventories. Risk pooling is defined as:

“A method often associated with the management of inventory risk. Manufacturers and retailers that experience high variability in demand for their products can pool together common inventory components associated with a broad family of products to buffer the overall burden of deploying inventory for each discrete product”.

- A supply network can reduce storage costs and the risks of stockouts experienced in smaller, decentralized warehouses by using a central warehouse to hold parts common to many products.

- There are tradeoffs to consider. Because the central warehouse may be further away from some production facilities than the smaller warehouses, lead times and transportation costs are likely to increase. Again, logistics have to be managed to improve the value of the overall system, not just one part of it.

7. Dynamics of Information and Goods Flow in Logistics and Supply Chain

If you recall, each supply chain has flows of goods (product or inventory) and information. Customer information flows through the enterprise via orders, sales activity, and forecasts. As products and materials are procured, a value-added flow of goods begins. The enterprise must have internal process integration, the best supply chain mapping technique when designing a supply chain network, collaboration between functions, and alignment and integration across the supply chain.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is logistics in simple terms?

It’s the planning and control of moving and storing goods, services, and information from origin to consumption so customer requirements are met reliably and cost-effectively.

Q2: How does logistics management differ from supply chain management?

Supply chain management covers end-to-end design, sourcing, production, and delivery. Logistics management focuses on transport, warehousing, order fulfilment, packaging, and related flows that support those goals.

Q3: What are the five key areas of logistics management?

Inventory management, transportation management, warehousing, order fulfilment, and demand planning—integrated to deliver the right product, place, time, condition, and cost.

Q4: Why is transportation such a large share of logistics costs?

Because moving goods frequently across distances requires assets, fuel, labour, and tight coordination—making transport the biggest cost driver in most networks.

Q5: What is the logistics value proposition?

Balancing service and total cost—meeting specific customer expectations at the lowest total logistics cost across all functions, not just the cheapest transport or storage.

Q6: How can information substitute for inventory?

Through accurate forecasting, precise tracking, cross-docking, postponement, and mixed shipments—keeping goods moving and reducing safety stock while maintaining service.

Q7: What is reverse logistics?

Managing the return, reuse, repair, recycling, or disposal of products flowing from customers back to suppliers—often turning a cost into a value-recovery opportunity.

Q8: When should we use 3PLs vs 4PLs?

Use 3PLs for specific services; choose a 4PL when you need an orchestrator for the entire logistics function and partner network, especially across complex global operations.

Q9: What is risk pooling in warehousing?

Consolidating inventory centrally so demand variability across locations offsets, reducing total stock required for a target service level—though lead times may rise for some areas.

Q10: Which tactics strengthen a logistics strategy?

Coordinate functions, integrate partners, replace inventory with information, streamline partner count, and pool risks—evaluating trade-offs via total logistics cost and service impact.

Q11: What’s the difference between “logistics meaning” and “logistics definition”?

“Meaning” is the practical understanding—moving and storing goods for customers—while “definition” is the formal description of obtaining, producing, and distributing the right materials in the right quantities and places.

Q12: Can you give a simple cross-docking example?

Like a hub airport: inbound goods are transferred straight to outbound transport with minimal storage, keeping inventory in motion and cutting handling time.